By Mir Muhammad Ali Talpur

The Baloch struggle is the most misunderstood of the struggles and it is not because of any fault of Baloch but because of the religion-dominated state narrative of Pakistani establishment. This has inculcated unreserved love for any name or ethnicity even remotely close to Muslim; the Pakistanis support Palestine, Kashmir, Rohingya and anyone else with any connection with Muslims. However, on these very grounds they consider Baloch as traitors and anti-Islam because they seek freedom from Pakistan.

The Baloch struggle is the most misunderstood of the struggles and it is not because of any fault of Baloch but because of the religion-dominated state narrative of Pakistani establishment. This has inculcated unreserved love for any name or ethnicity even remotely close to Muslim; the Pakistanis support Palestine, Kashmir, Rohingya and anyone else with any connection with Muslims. However, on these very grounds they consider Baloch as traitors and anti-Islam because they seek freedom from Pakistan.

How much and how far this country is Islamic is for all to see. The state narrative is accepted unquestioningly and this makes it easier for the state to manipulate minds and opinions. The Baloch issue is taboo for the mainstream media and the social media are generally either misinformed or adversely biased. The task on ground is difficult enough and the warped media coverage makes it doubly difficult. Very few columnists write about Baloch issues and even fewer papers defy the general trend to print them, even the blogs are not receptive.

The past, present of Balochistan have been determined by the fortitude and mettle of Baloch as a nation and its future presents new challenges and demands more advanced and unwavering approach from the Baloch as nation. The perseverance and the passion of Baloch nation is being put to test by the ‘dirty war’ that is being conducted against them. In the past three years more than 700 Baloch activists and common people have been abducted, tortured, killed and then dumped in different parts of Balochistan by Pakistani establishment and their proxy death squads to sow terror among Baloch population so they may refrain from demanding their rights. This brutality has failed to cow the Baloch into submission. The Pakistani establishment is expected to up the ante because economically bankrupt as they are, they need the Baloch resources and China is their partner in crime and promises to help them exploit Balochistan’s resources with the fancy schemes of Gwadar-Kashgar road and pipeline which has nothing to do with benefits for Baloch but is needed to provide an easy and cheap energy corridor to China.

An amnesty for the perpetrators of the ‘dirty war’ is being considered on pattern of Argentina and Chile. This amnesty would have people believe that the perpetrators do not already enjoy immunity; there has never ever been an arrest or a trial of those conducting the ‘dirty war’ but that isn’t surprising at all because in Bangladesh in 1971 millions were killed and hundreds of thousands of women were raped and there wasn’t a single prosecution. Expecting justice for Baloch is far-fetched but then this imposes a responsibility on all those Baloch who have any love for their people to raise their voices and highlight the Pakistani brutality wherever they are and however they can.

Baloch have to challenge the state narrative and present their narrative to the world without challenging the state narrative. Without challenging the state narrative they will never be able to make the world understand their struggle and their dream. Baloch also need to understand the underlying importance of presenting and preserving their unparalleled history of struggle for the future generations to learn from and the world at large to know the truth. Tweets on Twitter and status on Facebook as important, meaningful and profound they may be cannot and will not be an alternative to serious and dedicated literature.

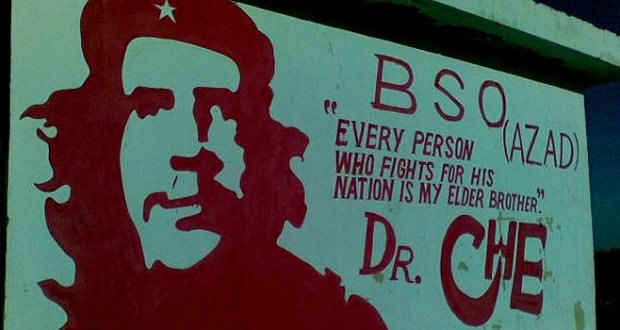

The culture of struggle has to be promoted to inspire the Baloch to persist and persevere with the struggle because Pakistan with all its resources is busy brainwashing Baloch with love of lucre and the allure of benefits of slavery. If these trying circumstances do not goad us into producing literature of culture of struggle and resistance raising the level of our struggle we will be failing in our historical obligations to the Baloch nation. The Baloch are struggling for their freedom; it is the goal they aspire to and the dream that they want to realize. It is easy for Pakistan, with the money available to it, to get recruits because of the immediate rewards submission and slavery offer while we have to inspire sacrifices for a dream, a dream most cherishable but yet most difficult to achieve and even more difficult to convince people with. We have to love the dream to be able to inspire people with that dream. I make a fervent appeal to all Baloch to unite for the dream for unless we unite it will always remain just that-a dream.

HISTORY

The Baloch are no longer bothered or concerned about giving a historical, political or economic justification for its secession from Pakistan but for those with an academic and historical interest in the subject I present the history.

The origins and early history of Baloch is shrouded in the mists of myths and folk lore. Some historians claim that they are Chaldeans; some insist they are Arabs as tribes of similar names still live there yet others say they are Turkoman. It is for certain that Baloch came here in migrations over time probably due to persecution as their choice of rugged terrain for their home suggests.

There is no definitive proof to support any of the presented theories but the fact that there are so many Baloch living in close proximity in the region extending into present day Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran who claim tribal, lingual, social and blood bonds means that they are a race in their own right. Moreover, their feeling of affinity for their brethren wherever they may be is itself an indicator of their historical oneness and also an expression of their desire for unity under their own rule.

The tribal lore abound with instances of co-opting of different individuals or clans into folds of tribe in times of need and also mention the battles fought to gain footholds in the areas where the Baloch tribes exist today. This co-opting may explain the language difference between Balochi and Brauhi. Balochi along with Dari, Persian and Kurdish is of the Indo-European stock; some historians say it originated from a lost language.

At different times attempts have been made to make a distinction between the Baloch and Brauhi in the hope that this difference would weaken the unity among them but this hasn’t succeeded. In fact after the Partition when Balochistan temporarily enjoyed the status of independence, the overwhelmingly Brauhi speaking majority of the members of Khanate’s Assembly voted to declare Balochi as the national language.

The Baloch find mention in the ‘Shahnama’ of Firdausi which indicates that they must have been an important enough a force to deserve a mention. Their history in Iran has been willfully been obliterated or misrepresented because of the hostility between the two races due to religious and political differences.

The Baloch folk lore mentions the arrival of 44 Baloch tribes in Makran under leadership of Jalal Han from Kirman and Seistan in the 12th century. After defeating the local ruler there the First Baloch Confederacy held sway there. Mir Ahmad Yar Khan suggests that the main group came to Makran, a smaller group went to Seistan and a group named Brauhi settled in Kalat. Death of Mir Jalal Han resulted in feuding between his sons and also conflict between Makran and Kalat.

Then we come upon Mir Chakar Khan Rind or ‘Great Baloch’ who ruled over large part of what is Balochistan today and had Sibi (Sevi) as its capital. A civil war between the Rinds and Lashars proved to be debilitating for the Baloch rule and in 1511A.D. Chakar migrated and he died in exile at Satgarah in Multan. The Baloch helped Humayun to regain throne from Sher Shah Suri and were given two estates known as Farakh Nagar and Bahadur Garh near Delhi. Many Urdu speaking Baloch migrated to Sindh after the Partition.

The Derajat Confederacy was founded by Sohrab Khan Dodai (1451AD) who was contemporary of Chakar Khan. The Derajats of Dera Ismail Khan and Dera Fateh Khan are named after his sons. Dera Ghazi Khan after Ghazi Khan Marlani Baloch though some say he too was son of Sohrab Dodai. This confederacy was weakened by its conflict with the Rinds and this conflict is preserved in form of ballads. The tribal inter-rivalry did not allow the Baloch to consolidate power in the way that Mir Nasir did for Khanate.

The Khanate began in true sense around 1666 AD with accession of Mir Ahmad Khan I to the Sardari there. He, according to Mir Gul Khan Naseer, was the first to rule Kalat like a sovereign and was continuously at odds with the Afghans. After his death Mir Mehrab was elected as the Khan and he battled Iranians to establish authority.

With Nasir Khan’s, the sixth Khan of Kalat, the golden era (1741-1795) of Khanate began. During that period he, more than any other ruler since or before, came closest to establishing a centralized bureaucratic apparatus covering all of Balochistan. He had a ‘wazir’ (prime minister) who supervised all internal and foreign affairs and there was a ‘vakil’ whose responsibility was collection of revenue from state lands and tributes from loosely connected principalities and chiefdoms. The two legislative councils, the lower chamber chosen by the tribes and an upper chamber of elders served in advisory capacity. It was, according to Nina Swidler, something between the kin-based tribe headed by an autocratic chief and the centralized bureaucratic state.

With death of Nadir Shah in 1747 Nasir Khan repudiated the tributary status to Iran. When Ahmad Shah established a new kingdom in Afghanistan Nasir Khan was forced to acknowledge Afghan suzerainty for eleven years but once he had established his military power he took on the Afghans militarily and fighting Ahmad Shah’s forces to standstill in 1758 and a peace treaty known as the ‘Treaty of Kalat’, accepting that Khan-e-Baloch will not pay tribute to Afghanistan, a policy of non-interference would be adhered to by both sides and all territories of Khanate in possession of Afghanistan would be returned to Khanate, was signed .

Nasir Khan is acknowledged as a hero by all Baloch for what he did to establish organized rule in Balochistan by Baloch themselves and his throwing off the yoke of Iranian and Afghan suzerainty. During his rule Kharan, part of Seistan (Iran-Afghanistan), Persian Balochistan, Derajat, Karachi, Makran, Chagai, Jacobabad and Quetta were part of Khanate. He assisted the Muslims of India against Marathas in the third Battle of Panipat (1761) and in 1765 helped Ahmad Shah against the Sikhs.

After his death in 1795 he was succeeded by his seven year old son Mir Mahmud Khan but administration was run by Akhund Fateh Mohammad, the ‘wazir’. During his rule Derajat were occupied by the Afghans, Makran and other Western Balochistan chiefs refused to pay tribute in short by 1810 Pottinger and others found the Khanate in chaos and anarchy.

Mehrab Khan succeeded Mahmud Khan in 1817 but he unleashed a very repressive policy against the chiefs and ministers and succeeded only in alienating the forces which could help him consolidate the Khanate. The British had begun their machinations in Afghanistan to consolidate its power in India and were busy playing games of intrigue to subdue the region. They wanted to send forces to Kabul to install Shah Shuja once again as King of Afghanistan and required a safe passage of its army of Indus via Bolan. The British tried to coerce and cajole Mehrab Khan to submission with threats and promise and eventually in early 1839 Mehrab Khan signed a treaty with Capt. Burnes for the safe passage and supplies.

The British wanted someone more pliable person as the Khan to help them realize their dream of ruling the region without hassle. The tribes didn’t always obey the Khan and there were attacks on the British forces by Marri tribe in Bolan Pass and adjoining areas. Using this as an excuse on 11th November 1839 siege of Kalat was laid by a well-equipped army led by Sir John Keane and on November 13th Mehrab Khan was killed along with his loyal supporters. For this act of defiance to British Mehrab Khan is considered a hero. Thereafter the British manipulated Balochistan affairs at will.

The Talpurs, a Baloch tribe, who came from the Bhurgrah area of Dera Ghazi Khan where some of them still live and are sometimes said to be of Marri tribe and sometimes of Leghari stock came to Sindh around 1670 AD and later ruled Sindh from 1783 to 1843. Mir Shahdad Khan, grandson of Mir Sulaiman Kako of Bhurgrah, who died in 1734, was the person who laid the foundation of Talpur rule in Sindh. His son Mir Bahram Khan was Prime Minister of the Kalhora rulers and his grandson Mir Fateh Ali was the first Talpur ruler of Sindh. They though being of Baloch origin could not form a common front with the Khanate and Dodai confederacy. Had these Baloch pockets of power united then probably Balochistan would have had a different history today.

In 1854, Britain entered into a treaty with the Khan, ruler of Baluchistan, in order to defend its territories against an external invasion from Central Asia and Iran. In 187O the British Government agreed to demarcate the border with the Khanate of Baluchistan. In 1871, the British Government accepted the Iranian proposal and appointed Maj. General Goldsmid as Chief Commissioner of the joint Perso-Baluch Boundary Commission, Iran was represented by Mirza Ibrahim, and the Khanate of Baluchistan was represented by Sardar Faqir Muhammad Bizenjo, the Governor of Makran. The Baluch delegate submitted a claim for Western Baluchistan and Iranians claimed most of Makran including Kohuk.

After several months of negotiations, Goldsmid divided Baluchistan into two parts without taking into consideration history, geography, culture or religion, and ignoring the statements of Baluch chiefs who regarded themselves as subjects of the Khan. The Iranian government in September 4, 1871, requested that a small portion of territory, including Kohuk, Isfunda and Kunabasta, be handed over to Persia. The question was referred to the Government of British India and General Goldsmid was consulted who changed his view and favoured the transfer to Iran.

In 1896 and 1905, an Anglo-Persian Joint Boundary Commission was appointed to divide Baluchistan between Iran and Britain. During the process of demarcation of the frontier, several areas of the Khanate of Baluchistan were surrendered by the British authorities, who were hoping to please the Iranian government in order to check the Russian influence in Iran. The agreement of 1896 was a clear violation of the treaties of (the agreement) 1854 and 1876, declaring the Perso-Baluch line to be the frontier of Iran and India. Under the treaty of 19O5, the Khanate lost the territory of Mir Jawa and in return the Iranian government agreed that this frontier should be regarded as definitely settled in accordance with the agreement of 1896 and that no further claim should be made in respect of it.

The final demarcation of Seistan took place in 19O4 by the British Commissioner, Sir McMahon, this Baluch-Afghan border or McMahon Line covers an area from New Chamman to the Perso-Baluch border. The boundary was demarcated by the Indo-Afghan Boundary Commission headed by Capt. (later Sir) A. Henry McMahon in 1896. The boundary runs through the Baluch country, dividing one family from another and one tribe from another. As in the demarcation of the Perso-Baluch Frontier, the Khan was not consulted by the British, making the validity of the line doubtful.

Though the power of Khanate crumbled from its former glory but yet the Khan was held in respect by his feudatories and chiefs of tribes and this forced the British to accord the Khanate a special status in their relations with Baloch. They also thought that sudden removal of an established authority and a symbol of unity would not serve their designs of using the region for its purposes but its relations with the Khanate were based on very narrow interests of British and any treaty or concession they gave or took was guided by that principle alone.

The Treaties of 1841, 1854 and 1876 and the subsequent alterations and the over-riding interests of Britain not withstanding all accepted the independent status of Khanate and continued till in 1947 when eventually Britain relinquished power with indecent haste causing misery to millions and jeopardizing the interests of Baloch and other nationalities which would have gone their own way in a more just and equitable world. ( Courtesy: www.viewpointonline.net)

|

Mir Muhammad Ali Talpur has an association with the Baloch rights movement going back to the early 1970s. He tweets at mmatalpur and can be contacted at mmatalpur@gmail.com |

Balochistan Point Voice of Nation

Balochistan Point Voice of Nation